Published on the LSE Europp blog on 14 March 2019

The rejection of Theresa May’s EU withdrawal deal on 12 March has given fresh impetus to those campaigning for a second EU referendum. But what are the odds that the outcome would differ from the 2016 referendum? If British voters were to be asked to cast another vote, would the Remain side gain a majority, as most supporters of a second referendum hope?

The standard way to answer these questions would be to aggregate individual, independent voting preferences, as reported in opinion polls. Yet, the recent experiences of opinion polling during the campaigns for the 2015 UK general election and the Brexit referendum have shown that this method might not necessarily yield accurate results. An alternative way is to rely on the so called ‘wisdom of the crowd’, by asking citizens themselves what the outcome of an election would be. These citizen forecasts focus on individual perceptions about others’ voting behaviour, with those perceptions averaged to form a forecast of an election result.

The underlying idea is that the process of public opinion formation is inherently a social process, and that citizens have a kind of knowledge or intuition about their surrounding social environment that cannot be captured by simply aggregating individual preferences. Indeed, in a recent study co-authored with Thomas Leeper, we found evidence that this is the case also in a referendum campaign. Around a month before the 2016 Brexit vote, a sample of British voters predicted the outcome of the referendum with a high degree of accuracy.

Citizen forecasts in the Brexit referendum

Between 30 May and 3 June 2016, we fielded an original survey through YouGov’s online Omnibus panel. A total of 3,385 participants were recruited with a quota sampling procedure that yields a sample representative of the UK adult population (England, Scotland, and Wales) with respect to age, sex, education, and geographical region. To measure citizens’ overall expectations about the referendum result, we asked them “Regardless of how you yourself intend to vote, what percent of voters do you anticipate will vote for Britain to leave the European Union?”

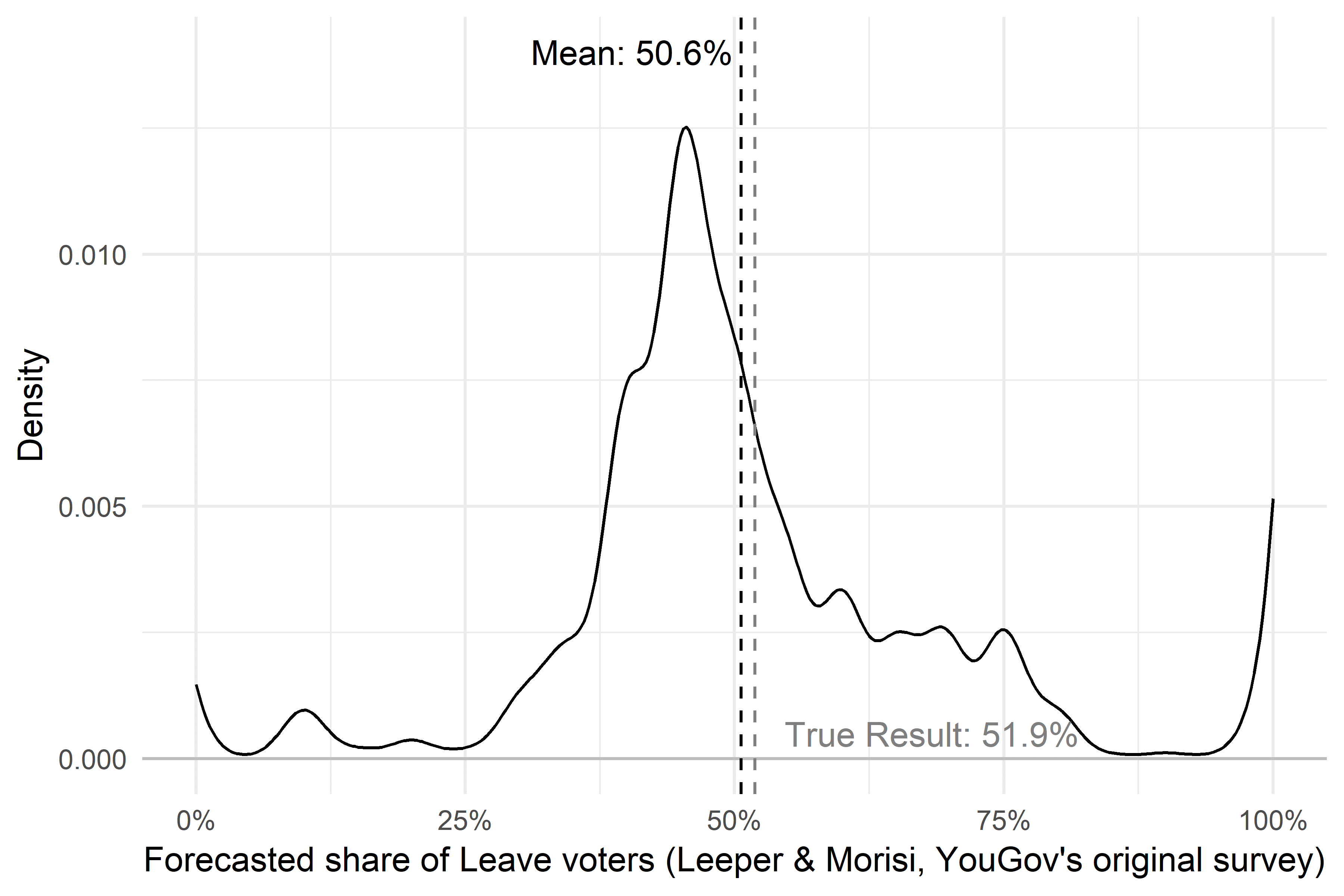

Figure 1 shows a density plot of the forecasted share of “Leave” votes in the Brexit referendum. The horizontal axis shows potential results of the referendum; higher peaks indicate where more respondents thought the outcome would fall. Despite a peak of the distribution below 50 percent, the average, weighted forecast slightly favours the Leave side (at 50.6 percent), falling short of the true referendum vote share for Leave (51.9 percent). A significant share of respondents forecast a 100 percent chance of a Leave vote, while a few others predicted a 100 percent chance of a Remain vote. However, if we trim the variable including only those who reported forecasts above 10 percent and below 90 percent, the average forecast still remains above the key threshold of 50 percent, slightly shifting to a predicted share of 50.3 percent of Leave votes.

Figure 1: Forecasted share of Leave voters (YouGov’s original survey, 2016)

British Election Study

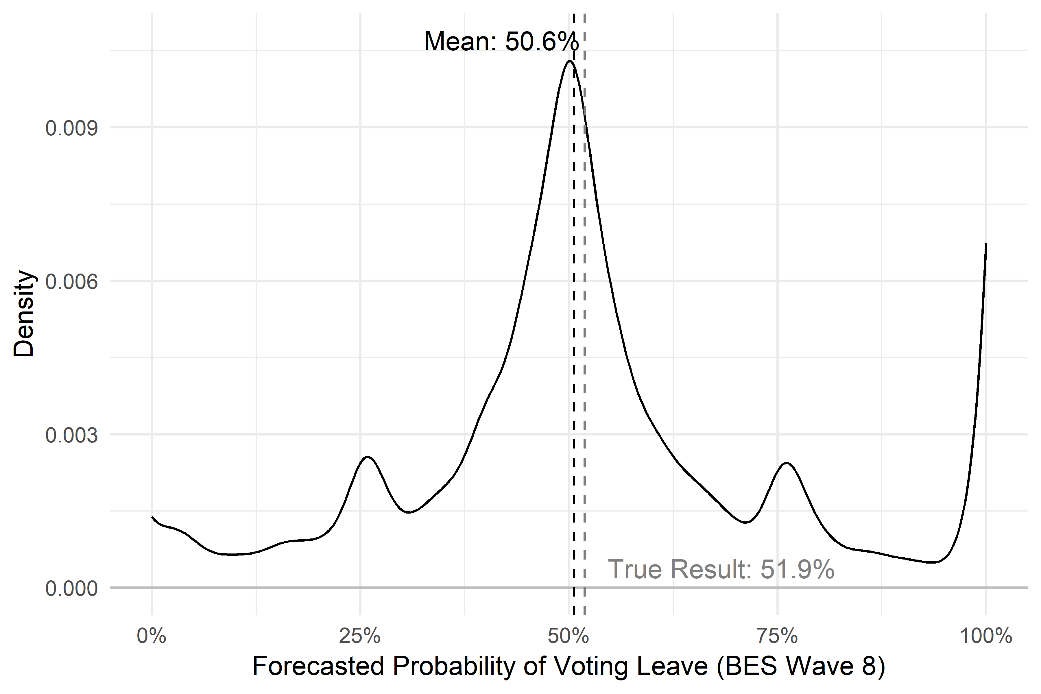

We replicated the analysis using data from Wave 7 (14 April-4 May, 2016) and Wave 8 (6 May-22 June, 2016) of the British Election Study (BES) Internet Panel. Both waves included the question “How likely do you think it is that the UK will vote to leave the EU?” The respondents could choose a number on a 0 to 100 scale, with zero labelled “UK will definitely vote to remain in the EU” and 100 labelled “UK will definitely vote to leave the EU.” Although this question asks to report a probability and not an expected percentage of voters, the results are substantially the same as our results. As the plot in Figure 2 shows, the average forecasted probability of voting leave in Wave 8 of the BES Internet Panel was again 50.6 percent. If we focus, instead, on the data from Wave 7, the predicted probability of a Leave vote slightly declines at exactly 50 percent, which is still a pretty accurate result considering that the survey was conducted around two months before the vote.

Figure 2: Forecasted probability of voting Leave (BES Internet Panel, Wave 8, 2016)

These results confirm that on average citizens can provide accurate forecasts even of high-stake referendum campaigns, in line with previous studies showing that voters accurately predicted the results of both U.S. presidential elections and UK general elections. However, our study indicates also that important differences exist within the electorate. In particular, we find that older people, wealthier people, and those with high education provided more accurate forecasts than their relative counterparts. On the other hand, those who intended not to go to vote in the Brexit referendum provided significantly less precise forecasts than either Remain or Leave voters, thus suggesting that involvement in politics proves relevant for forming an accurate picture of the social reality.

Can citizens predict a second Brexit referendum?

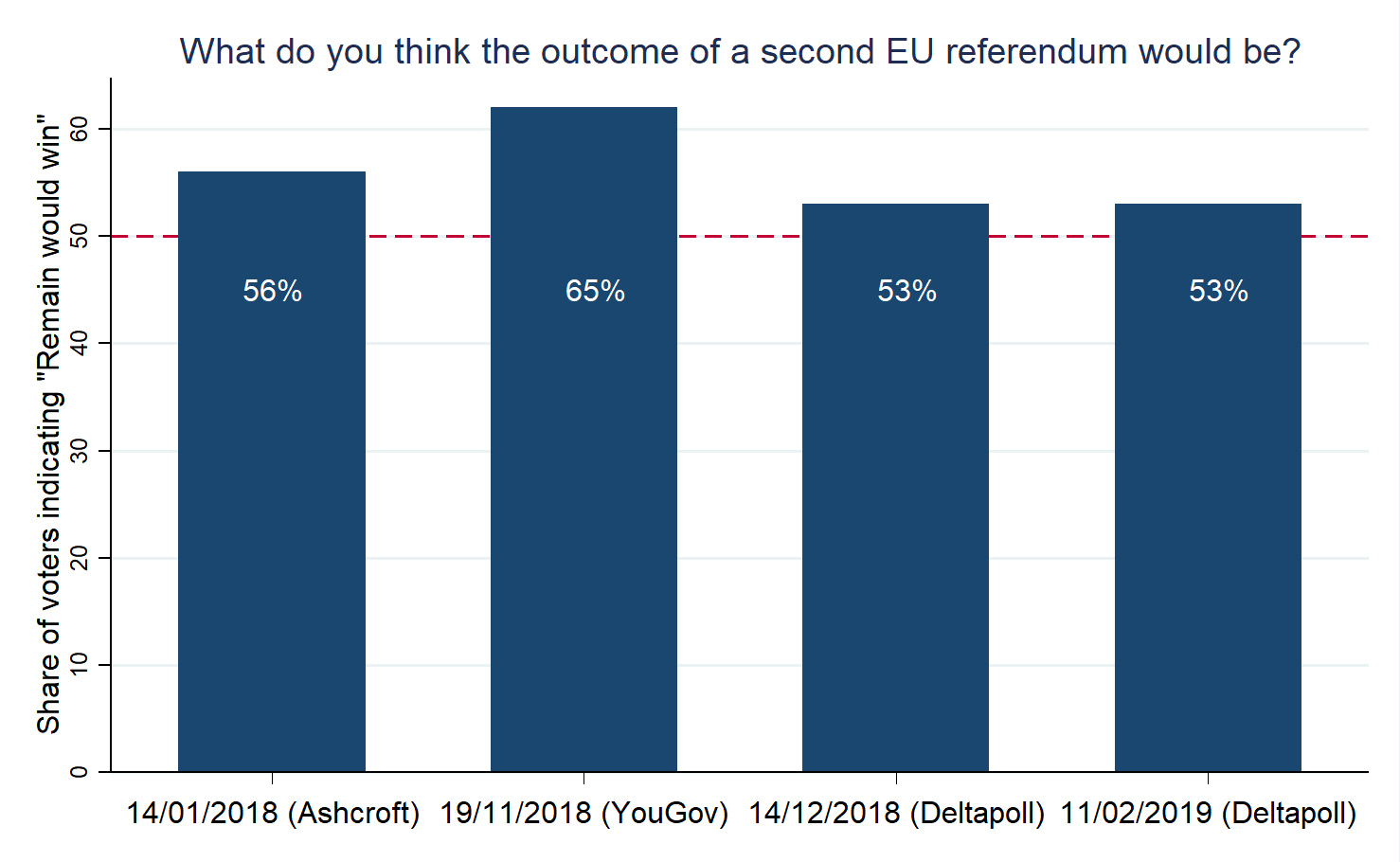

Since the beginning of 2018, we have found four opinion polls that include a simple form of citizen forecasts. The respondents were asked whether in their own opinion it was more likely that either the Remain side or the Leave side would have won in a second referendum. Figure 3 illustrates the results: according to the data retrieved from the What UK Thinks website, in each opinion poll, a majority of voters predicts that the Remain side would win. It is important to keep in mind, however, that a large share of undecided respondents – ranging from a quarter to a fifth – has been excluded, and that a result of just below 50 percent would still be within the margin of error of the latest survey by Deltapoll.

Figure 3: Citizen forecasts of a second Brexit referendum

Note: Data retrieved from https://whatukthinks.org/eu/

In sum, our results indicate that a possible way to predict the outcome a second EU referendum would be relying on citizen forecasts. If Article 50 is extended and British voters have a second say on the Brexit process, pollsters should consider adding questions on voters’ expectations about the outcome of the referendum. While relatively inexpensive, such questions could yield potentially more accurate forecasts than simple aggregation of individual preferences, especially if pollsters were to give more weight to respondents who are generally more accurate.