Published on The Monkey Cage (Washington Post) on 10 December 2016 (co-authored with Juan Masullo)

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos is receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo today, in recognition of his four-year effort to guide peace negotiations with Colombia’s largest rebel group, the FARC.

The October announcement about the prize came just days after Colombians rejected a referendum on the historic peace agreement to end the armed conflict that has plagued the country for half a century. In late November, the two sides pushed through a revised peace deal addressing some of the concerns of those who voted against the referendum. Santos avoided another referendum by getting the senate and the lower house to approve the new pact.

Referendums are tough to push through

The outcomes of referendums — whether in Colombia, or the June Brexit vote or December’s Italian referendum — make it clear that getting people to vote for government initiatives is harder than one would expect.

Our research, conducted shortly before the October vote in Colombia, shows that one way to increase support among voters is to stress the opportunities that the proposed initiatives would bring, rather than underscoring the risks associated with its failure. Our study reveals that Colombians were more likely to support the agreement if they read positive messages that framed the peace deal as an opportunity for change. This was true particularly when these messages were backed by an actor that the public can hold accountable, such as the government.

The power of information

As several commentators highlighted, information on the 300-page peace deal played a key role in driving the results of Colombia’s Oct. 2 referendum. To test the impact of information on people’s attitudes and voting intentions, we conducted an experiment in the short time frame between the signature of the peace agreement in Cartagena (Sept. 26, 2016) and the day of the plebiscite (Oct. 2, 2016). We fielded responses online, using a sample of 669 eligible Colombian voters. Our participants had a higher level of education than the average and included a larger share of yes voters compared to the actual outcome on Oct. 2.

We randomly exposed participants to different easy-to-digest pro and con arguments. Each of these statements was around 70 words, and reflected the arguments and language used by either side in the campaign: e.g., “the agreement is a historical opportunity to end violence in the country,” and “not supporting the agreement would take us to a blind alley and eventually lead us back to armed confrontation.”

So our participants read texts that highlighted either the opportunities or the risks of the yes and the no campaigns. In addition, some survey participants read a pro-opportunity argument that explicitly stated that Santos and his government endorsed the peace agreement as a historical opportunity.

Framing yes as an opportunity

We found out that “pro” arguments both increased the likelihood of voting yes and the general support for the peace deal, and that this was especially the case when we framed the yes argument as an opportunity. Survey participants who read a short text highlighting the opportunities of the agreement were significantly more likely (13 percent) to vote yes than those who did not read any text.

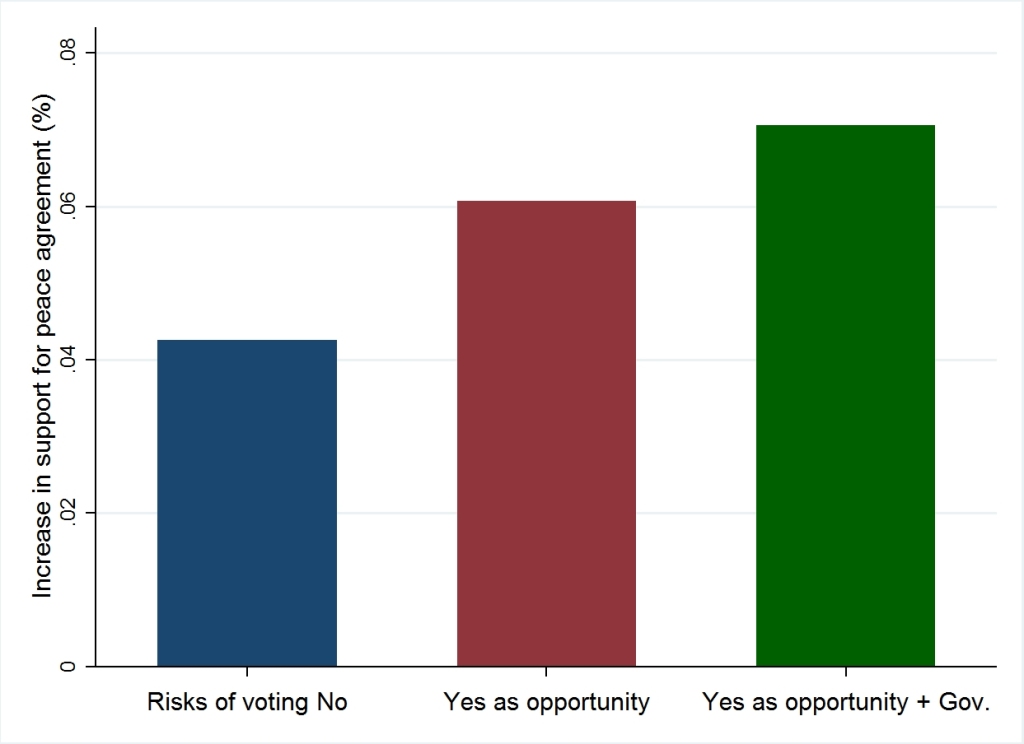

Figure 1 illustrates that all three “pro” arguments increased support for the peace agreement, as measured on a 0-10 scale. But this increase is larger when “pro” arguments stress the opportunities of the deal, and especially when these opportunities are backed by the Colombian government (shown in the green bar).

This finding is surprising, since opinion polls indicated Santos’s popularity was not particularly high at the time of the plebiscite.

An issue of accountability

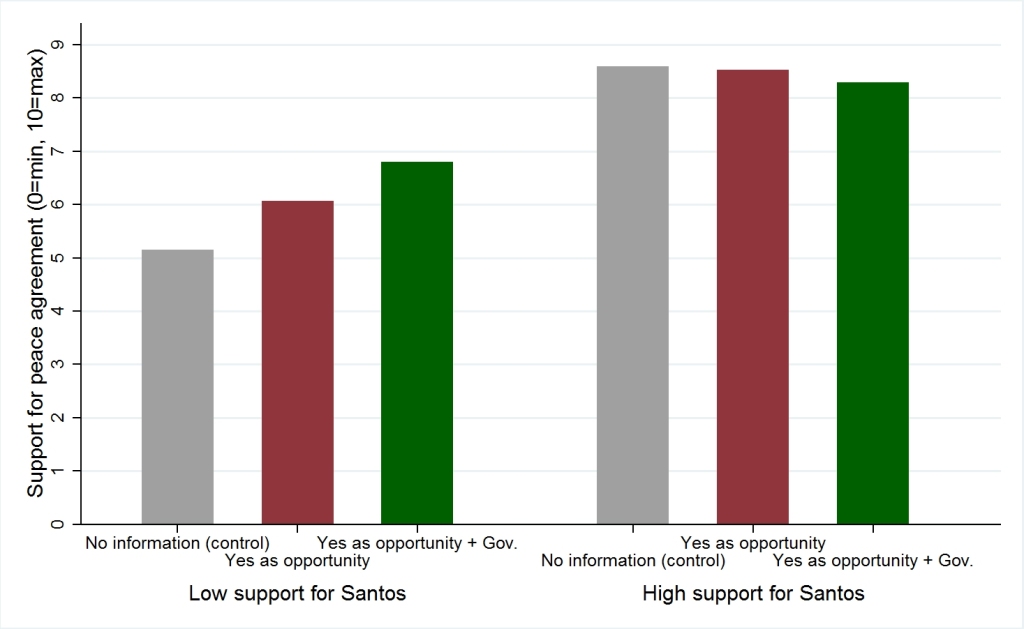

To test whether faith in the president drove the observed effects, we split our participants between those with low and high support for Santos. This revealed unexpected findings: Pro-opportunity arguments coupled with a government endorsement (the green bars in Figure 2) increased support for the peace agreement among those with lower support for Santos.

Figure 2: Effects of pro arguments on support for peace agreement, broken down by support for Santos Data: Juan Masullo and Davide Morisi. Note. Support for the peace agreement measured on a 0 (low) to 10 (high) scale. Median split of the participants on a 0-10 scale of support for Santos. Figure: Juan Masullo and Davide Morisi

We suggest that accountability, not popularity, drove these results. The arguments in our survey stressed opportunities that would be realized in the future, but that would not come automatically by voting yes. The effects of these arguments, therefore, will probably be stronger when endorsed by someone who can work toward their effective realization and, more importantly, by someone who can be held accountable for progress for peace. This is a key insight for those tasked with building sustained support for the peace deal in the years to come.

The take-aways travel beyond Colombia

But stressing these opportunities might not be enough. The second takeaway point is that voters may look for an accountable person behind the proposed initiatives. Having someone who has the capacity to work toward the effective realization of the deal can build support, even if that person does not enjoy high levels of popularity.

The sustained support of the Colombian people will be important for successful implementation of the revised peace agreement. Citizens will be looking for signs that this latest deal is a solid step toward long-lasting peace. Framing it as an opportunity and the government explicitly endorsing it might be part of the recipe for giving peace a chance.

Juan Masullo is a pre-doctoral fellow at the Program on Order, Violence and Conflict at Yale University and a PhD candidate at the European University Institute. His research focuses on contentious politics, with a specific focus on civil war dynamics.

Davide Morisi holds a PhD from the European University Institute. His research focuses on public opinion and political behavior, with a specific focus on referendum campaigns. He tweets at @dmorisi.